|

A

STOP

ALONG

THE

WAY |

|

The last thing he remembered was idly thinking that sparring with Simon Locke was actually becoming something to look forward to.

No, the actual last thing he recalled was the damn deer in the middle of the road.

Now police chief Dan Palmer was standing at the side of a dirt road with the nose of his police car kissing an oak tree and realizing he hadn’t forgotten the vocabulary from his stint in the Army.

Dammit, even when Locke wasn’t around he was causing trouble.

Shaking his head, he reached into the car, keying the speaker of the police radio. “Kingsbridge, this is Dixon Mills. I’ve run into some trouble.”

A blat of static was his answer.

“Well, this is just my day, isn’t it?” he said aloud to the trees around him.

It was the sleepiest of cloudy mid-November days and Palmer had left his deputy Bert "in charge of the store" with dire warnings to telephone if anything went wrong. It was not a distrust of Bert, but more that he was so possessive about his home town that he rarely let himself be off duty for long. Besides, this was a business excursion; he'd been on his way to the neighboring community of Kingsbridge to consult with their officers about a string of home burglaries in the community that appeared to be heading in the direction of Dixon Mills. He'd figured taking seldom-used Harriman Lane as a shortcut would save him time.

He shrugged. He had his jacket, a hat if he somehow needed it, and he was only a few miles out. As he reached into the police car to get his hat, he could feel the crackle of the paper in his shirt pocket. He set his teeth and ignored it for the moment.

It was only when he turned around that he saw the dog.

At first he was on his guard. It was a big dog, and so close in appearance to a wolf that he started at first. Even a big feral dog would have been a problem, despite his service revolver and ability to defend himself.

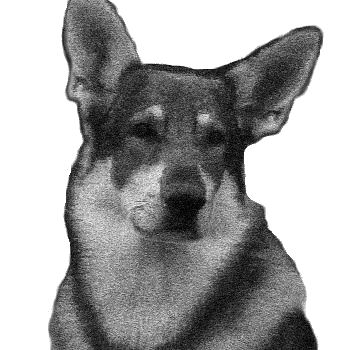

But this was definitely a dog, not a wolf, with the mellow dark eyes of a dog. Palmer realized the animal was a German Shepherd, but it had taken him a few minutes to recognize it, as it was not the familiar black-saddled and -muzzled animal like the dogs who played Rin Tin Tin on television when he was younger. Instead, it was mostly black, with a patch of brown on its neck like a short cape, and silver-grey markings elsewhere, and most extraordinarily, a white mask on his muzzle running under its head. Pale marks over the eyes made the dog look as if it had white eyebrows, and it had them raised in an inquiring manner, as if he were checking Palmer out as well.

Then it rose slowly and sauntered to Palmer’s side, revealing the fact that it was male, slowly waving the brush of his tail, and sat down before him, offering one massive right paw.

For the first time that morning, since the postman had handed him his mail and the deer had put a spanner in the works, Palmer cracked a smile, crouched down, and shook the dog’s paw. “Good boy. Your owner around here somewhere? I could use some help.”

The dog simply looked inscrutable. Palmer noticed he was wearing no collar, but then many country dogs didn’t wear them. “C’mon, boy, go home. Go home!”

The animal’s tail waved again, and he moved purposefully up the road. Palmer locked the doors of the car, and followed him, where the dog adjusted his gait to accommodate a two-legged companion.

Despite the delay, Palmer started to enjoy himself. He spent so much time trapped inside the car or inside the ‘copter that walking in the fresh air without being on the trail of some miscreant raised his spirits rather than blunted them. It was cool and pleasant, cold enough to wear a jacket but not to need to button it, and the leaves were past peak, some still rattling faded copper on the trees that surrounded either side of the road, others swirled on the ground in browning heaps. Now that the brush was leafless you could see through the tree trunks, noting boulders and horizontal lines where older trees had fallen. He could smell leaf mold, old wood, and the touch of winter in the air, and it brought him back to his school days when he had also marched up country roads with a dog at his side.

He smiled ruefully as he looked sideways at the handsome Shepherd pacing beside him. Butch had some German Shepherd in him, but it was mixed with other large breeds; he had been heavier built with a stout muzzle, one of his erect ears lopped over halfway down, and he had been the sleek brown of a cinnamon stick, with white toes on his hind legs. Butch had ostensibly been the Palmer family dog, but he had stuck like a burr to the eldest boy, and he was a daily companion on campouts and woodland adventures, shared with his best buddy Tim Fournier. When they played cowboys, Butch was a faithful steed (if one not large enough to be ridden), when they played war, he was the messenger dog. Mostly, though, he’d been a friendly ear, a prodigious rabbit hunter, and a somnolent fishing companion.

All the world was in front of them the summer Palmer was thirteen, a summer full of anticipated rabbit chases, swimming hole excursions, blackberry picking. A day or two before school was done for the year, he'd come walking into the house puzzled because Butch had not come racing out to meet him. It was his mother who had to tell him that Butch was gone—he'd chased a rabbit out the front gate and a passing truck had struck and killed him. They buried him in the woodlot out back and Dan got a summer job working for old man Morgan instead.

Jeez, where did that come from? He hadn't thought of old Butch in years.

"So what's your name anyway," he asked the dog idly. "King? Chief?" He ran through a string of typical German Shepherd names and had just paused after "Prince" when the dog halted, alerted, then plunged into the woods.

Dan figured the animal was heading home, but in a few minutes he'd circled back, gave one sharp bark, and did that very plain dog ballet that meant "follow me."

Dan glanced at his watch. His schedule was blown anyway. "What the hell."

It was easier for the dog, leading him through the brush, because he leaped easily over obstructing fallen saplings, rocks, tangled old fence wire. Dan worked about them more carefully, his boot soles sliding on leaf mold and broken twigs, noting he was approaching a sagging barbed-wire fence surrounding cultivated land. There was a broken-down old shed in sight just inside the fence, and the dog huffed as he saw it, because from behind the old shed came a weak cry.

He clambered over the fence as easily as his canine companion had cleared the wire, and came around the corner of the shed to find the dog gently nosing a tall, elderly man who was seated on the ground, smeared in mud and leaf mold.

The old man glared at him. "Nice of you to finally show up!"

Palmer bit back a retort. It would make him feel better to be sarcastic to the cranky old goat, but it wasn't professional, and maybe the old guy was hurt badly enough to justify being rude. So he only said mildly, "Sorry, but I didn't know you were here. Are you hurt?"

"Ain't that your police dog?" the elderly man asked testily. "I told him to go fetch someone."

"He's not my dog. I met him on the road. Good thing I followed him, too. Is it your ankle?"

Somewhat mollified, the man grumbled, "Turned it in a damned gopher hole."

Palmer switched positions and started examining the man's ankle with gentle hands. "Ouch! You a doctor, too?"

"Police officers do know first aid," Palmer said in a soothing tone he didn't feel. The man was wearing a faded, frayed Army jacket, so he took a guess and said, "Out checking out your farm, Sarge?"

"Getting a post hole digger out of my shed," the man admitted, sounding pleased. "Earl Bellaby's my name." He noticed Palmer's uniform for the first time. "Dixon Mills! What are you doing way out here? Chasin' someone?"

"Car died on the shortcut." Palmer circumvented his embarrassing predicament. "Walking for help when I met the dog. He led me here to you."

"Smart one," Bellaby agreed, making a querulous coaxing sound to the German Shepherd, and the dog obliged by offering his paw.

"Well, I'm no sawbones," Palmer said after a few minutes, "but this feels like a sprain at most. Bet it hurts like hell."

He helped Bellaby to his feet and after a few minutes of the elderly man wincing, he managed to set his foot down gingerly and walk—or rather limp—on it.

"Would you like me to walk with you back to your house?" Palmer asked diplomatically. What the old guy looked like he needed was a crutch or a hand, but he wasn't about to get snapped at again.

Surprisingly, Bellaby agreed, but added, "Might as well get that post hole digger while I'm down here, seein' as I messed my leg up for it."

"I'll get it," Palmer offered routinely, but the old man jerked his head at him in a negative gesture, opened the door to the shed and rummaged about with his hand for a minute. The German Shepherd stuck an inquisitive nose in the doorway as he did.

"Get out of the way, dog, or I'll take back what I said about you being smart." As Bellaby extracted the post hole digger, Palmer got the briefest impression of disorder in the shed: spades, burlap sacks, rusting fox traps. It was possible that the shed was even older than the superannuated codger.

The three of them trudged slowly up to the old farmhouse, which Palmer noted was not much better kept up than the shed, sagging to one side like a spavined horse, but then that's the way farms were. They ate up your spare money for new equipment, new fences, new livestock, and that new coat of paint and the hole in the porch just had to take second place, while a refrigerator to replace the old icebox was ratcheted back to fourth or fifth place while the farm wife just sighed and put up with it. After his brief burst of conversation, Bellaby settled into a moody silence and Palmer was left to watch the big dog flick his ears this way and that, sniffing toward the barn and the woodshed.

An old steel blue Pontiac sedan with rusted patches over both sets of wheels was sitting in front of the house, and as the two figures approached, a husky younger man with bright red hair, wearing a plaid hunting jacket over worn blue jeans, came from around it in alarm, raising an arm.

"No cause to worry, Johnnie," Bellaby called loudly. "This is Chief Palmer, works over to Dixon Mills. Helped me back from the lower forty. Twisted up my leg in a gopher hole. Chief, this is my nephew Johnnie. Comes by to help me with big projects, like putting in new fence."

Palmer thought sarcastically that Johnnie wasn't coming often enough if the property was in such bad shape, then took note of the German Shepherd. He had halted in mid-step to regard the nephew, then cautiously waved his tail.

"Lemme give you a hand, Uncle Earl," Johnnie said, offering the old man an arm. "Nice dog, Chief Palmer."

Palmer swallowed a "Not mine," and just commented "He is," and helped Bellaby onto the creaky porch, where the elderly man nodded. "Beholden to you. Thanks."

Palmer nodded in return and headed out to the road via the rutted dirt driveway with the big dog tagging behind him. "Still hanging in there, eh, boy?" His mouth twisted into a smile. "Have to call you something...how about Duke?"

The dog gave a soft "Uffff!" under his breath. "Duke it is, then."

It was no time at all under his ground-eating stride until the dirt road turned to pavement and he was on the streets of Kingsbridge. At first came the businesses: the feed store decked out in cornstalks and Indian corn, a tractor dealer, a small vintage 1950s car dealership with Thanksgiving decorations painted on its showroom windows, then next neat houses with long front walks and dormant flower gardens and bare pergolas at the side, some of the doors decorated with wheat wreaths. Taller buildings appeared in the distance just a horn beeped behind him. Palmer turned, startled, to see Charley Fisher smiling at him from the seat of his police car.

"What's up, tenderfoot?" Fisher joked as he drove abreast of him.

"My feet hurt," Palmer said dourly.

"Saw your car down by the shortcut, so I started running up the roads looking for you," Fisher said cheerfully. "You and that tree ought to take up some dancing lessons."

"Har-har," Palmer scowled, put his hand on the door handle, and turned to Duke to tell him to jump in.

The dog had vanished.

Fisher watched Palmer pivot on his feet, scanning the landscape around him. "What's up, Dan?"

"There was a big dog following me most of the way here from my car." Palmer explained, as he continued to squint at the golden meadows and the yards and homes around him. "Big German Shepherd. No collar, didn't know who he belonged to. I thought I'd look around for the owner, and, frankly, if he didn't have one, I was going to take him home myself. Smart dog. Led me to..."

"Mobile One," crackled on Fisher's radio. "Come in, Mobile One."

Palmer shrugged, then got in the front seat of the car with his colleagues as Fisher keyed his mike. "Mobile One here."

"How's it going, Charley?" asked the dispatcher. "Did you turn up old Dan?"

Palmer snatched the mike from Fisher. "Yeah, old Dan here, you ancient radio jockey."

A hearty belly laugh emerged from the radio. "Glad you're all right, old timer."

Fisher took back his radio mike. "Found him walking into town. Had some car trouble on Harriman Lane. Dan, did you see your dog?"

"Not a sign," Palmer admitted. "Guess he belongs to someone here in town after all."

"Julius, we know a couple of German Shepherds in town, don't we? The Pollocks have one, and I think the Karvitz family has two of them."

"This one was different," Palmer continued, and described the dog. Finally Julius Sherman came back on the radio.

"All the police dogs around here are the tan kind with the black saddle. I haven't heard of anything like a black-and-silver dog. You sure it was a Shep?"

"Looked like one," Palmer said briskly. "Whatever. I'll see you in a few minutes, Julie."

Fisher sang sweetly into the mike, "Julie, Julie, Julie, do ya love me? Julie, Julie, Julie, do ya care..."

"Knock it off, Charley," came the stern response, and the radio cut off, and Fisher grinned at Palmer. "I've been singing that to him for a year now."

"And he hasn't decked you?" Palmer riposted, trying to concentrate on his original task, but it didn't keep him from looking backward out the passenger-side window one more time.

Kingsbridge's police department was in an all-in-one town services building that had once been a wealthy mill owner's showplace. The town council saw that it was repainted often and any obvious building defects were corrected, but the old place looked like a dowager gone to seed, a little askew to the south, all painted in off-white rather than trimmed out like the painted ladies it emulated. Some of the porch scrollwork posts had been broken and were replaced with plain one-by-twos. The town council's offices and the fire chief's office were all upstairs, and the police had the first floor to themselves, except for a small corner where Dorothy Murray ran the post office nearly single-handedly. She waved at Palmer when he came in and then went back to sorting mail.

Sherman looked up from his battered old metal desk where he was pecking away at a manual typewriter. "The prodigal returns!"

"Look, if you two don't want my help, I don't have to stay," Palmer said reprovingly.

"Good luck walking," Sherman replied cheerfully.

"I called my brother Billy to look at your car," Fisher said good-naturedly. "Didn't look like anything major to me. Those Chevys are like bulldozers; it's hard to kill 'em."

Palmer looked dourly about at the honeycomb paper turkeys and Indian corn scattered on the divider between the battered wooden seats for visitors and the police officers' desks. "You guys going in for 'Better Homes and Gardens' now?"

Sherman snorted. "Dottie's doing. She's scattered decorations all over the place. Says it looks friendlier."

"Yeah," Fisher said idly, "not like a big-city police department would be."

Palmer and Sherman both stared at him, but the former with a glare that could have removed paint.

"So," Palmer said, almost through his teeth, "what do you have on these break-ins?" With a stiff gait he pushed through the swinging divider gate, then sat rigidly at the nicked conference table and yanked out a small spiral-bound notepad and a pen from his shirt pocket.

"Not much more than what we told you on the phone." Fisher answered, easing into the chair next to him. "Eight places have been hit. They run the gamut from farmhouses to the Pruitt place—you know how loaded that old guy is. The burglar takes anything small of value, mostly jewelry, transistor radios, small televisions, small appliances. No connection between the victims."

Sherman added from his desk, still eyeing the two of them warily, "You forgot to tell him the weird thing."

"The weird thing," Fisher amended. "There's always some little personal item missing. For instance, Mrs. Barry had a cheap ring stolen, along with her diamond earrings and other jewelry. Perry Stalmaster had a photo stolen, of all things, one good photograph of his sister who died back in 1959. Old Mrs. Felix had a plain old woolen scarf from Woolworth's taken. She said it was over thirty years old and moth-eaten. Here's the list."

Palmer read the notes half-typed, half-scrawled on a lined tablet. "A fox fur wrap, a sapphire ring...and a tea pot from the five and dime? Sounds crazy."

"Check out the last one."

"Two transistor radios, a portable television, a silver wine salver...what the hell's a salver?"

"Serving tray," Sherman responded.

"A silver wine salver, a pair of pearl earrings and...a Cracker Jack ring?" Palmer looked up. "A Cracker Jack ring?"

"I kid you not. Mildred Churchfield. Said it had sentimental value."

Palmer sat back in his chair. "What kind of clown steals things of value that can be pawned plus a Cracker Jack ring and an old snapshot?"

"I agree. That's why we were hoping you'd help us ask a few more questions."

Palmer shook his head. "Sure, why not? That's one hell of a list. Look, I had an idea...I want to start-"

"Hey, man," and a lean, blond young man in a mechanic's grease-smeared outfit and a face that made him look like Charley Fisher ambled through the door, "got your car out front."

"Good work, baby brother," Fisher said affectionately.

"I didn't think the dent was that bad," Palmer said. "Why wouldn't it start?"

"It isn't that bad," Billy Fisher answered, shaking his head so that his ponytail flashed back and forth. "Distributor cap came loose. Bumper took most of the bang, but you're going to need body work."

"Another session with Howard Meserve and the town council for appropriation money. Ahh, happiness." He looked at Billy speculatively. "You didn't see a big, mostly black dog hanging out back at my car, did you?"

"Not a one. You got a dog now?"

"Nah. Stray—I guess—I met on the road. Led me to the funniest old goat, Earl Bellaby, who'd twisted his ankle. I helped him back to his house."

Fisher laughed. "Old Earl. Yeah, he's a character all right."

Sherman finally concluded his typing with a smart smack of the carriage return. His nimbus of silvering red hair was set aglow by the sunlight through the big windows. "You met Casanova Earl?"

Billy practically goggled. "Casanova...we're talking about old beanpole Earl, right, that lives on that back road to Dixon Mills?"

Sherman gave another belly laugh. "You wouldn't know it to look at him, but when I was a boy, old Earl was the biggest tomcatter—that's what we called 'em then—in the county. He had ladies on a string from here, from Dixon Mills, from way out Briarton way. He was a sharp dresser back in those days and he looked a little like...uh, what was that dark guy," he snapped his fingers, "you know, the movie star...Robert Taylor. Yeah, he looked a little like Robert Taylor. Women used to fall all over him. Especially when he came back from the service. Gals can't resist a good-looking guy in a uniform."

The expression on Billy's face said "pull the other one," but Sherman held up his hands. "Go ask Milt Grossman at the hardware store if you don't believe me. He was Earl's best buddy. Better yet, Dan, you go ask Miz Rhodie over in Dixon Mills—I hear she was one of his sweeties..."

Palmer threw up his hands. "No, no, I'm not that interested in knowing. So, as I was saying..."

"Anyway, here's your list, Dan. These are the homes that were hit heading toward Dixon Mills. You can talk to them as you're heading back and let us know what you found out tomorrow." Sherman handed him a list of three families that lived over the Dixon Mills line toward Kingsbridge. "I included the files so if you find out something different than what we have, you'll see it right away."

"Okay, that works out." Palmer would have preferred looking at the Kingsbridge sites which were the beginning of the crime spree, but since it wasn't his investigation, he didn't suppose he could complain. His eyes flickered to Billy. "I suppose you've repaired the damage you did hot-wiring my car, right? I assume that's how you got it here, since I have the keys."

"Easy as pie," Billy laughed, waved a careless hand, and departed.

Fisher said with an easy smile, "A job did that boy a lot of good. Thought he'd be stuck in juvie forever."

"He looks like he's taken to it alright. Anyway, I'll talk to you tomorrow," Palmer said, suddenly in a hurry to get on his way, hoping to outrun the question he was afraid would pop up. Fisher beat him to the door.

"How's that other thing going, Dan? You thinking about it?"

Sherman had gone back to his report, but glanced up speculatively. "Charley, looks to me like Dan was hoping that was something you wouldn't bring up. What's up?"

"Big mouth," Palmer scowled at Fisher. He indicated him with a thumb. "Mr. Loudspeaker over there and I have a mutual friend in the city, a guy we went to police training with. He's on the force. Offered me a job. Detective Lieutenant."

Sherman whistled. "Not an offer you take lightly. Dixon Mills can't ever pay you the salary they'd offer."

"I'm not hurting for money," Palmer said, almost too sharply, then bit his lip. "But it is a good offer. Opportunity to learn something new."

"If you don't want it, Dan," Fisher said, semi-seriously, "I'll take it."

"C'mon, they won't offer it to you," Palmer scoffed. "You can't even keep a secret. Anyway, I'll talk to you tomorrow after I've done these interviews."

He stalked back out to his car rattling his keys in annoyance. The crackling paper in his pocket was louder than drums. The arrival of the formal envelope had been inauspicious; it was only when he read the letter that his heart had given a leap, but later he wasn't certain if it was due to excitement or dismay. Captain Robert Piekowski was offering him a detective's job—oh, not in command at first, but the captain had assured him that the situation probably would not last long. The implication was that if he kept his nose clean, followed orders, and followed his instincts as a police officer, command would come in time.

He headed back toward Dixon Mills, having almost forgotten his canine encounter earlier. He stopped at the first two homes, essentially getting the same information Fisher and Sherman has earlier. They hadn't told him to re-examine the points of entry and where the items had been stolen from, but he did so nevertheless. Finally he arrived at the Churchfields, parking in front of the deep front porch dotted with old tables and chairs and scattered autumn leaves. The Churchfields raised goats for milk and cheese, and Palmer could hear the soft bleating coming from the pastures behind the barn. The house was a clapboard farmstead dating back to the late 19th century, faded to a uniform grey with chipped black trim.

An elderly woman was sitting in a faded red rocking chair draped in a crazy-quilt of a knitted afghan, leisurely rocking back and forth, watching him with a curious, birdlike face with bright blue eyes. He was emerging from the car and wondering if this was Mildred Churchfield when a stout middle-aged woman came out the front door, laid a brief hand on the elderly woman's shoulder, then came down the concrete front steps to meet him. He was certain he knew her from somewhere.

"Dan Palmer, how are you? Do you remember me? I was at school with you. Betty Adamson."

His mind clicked. "I do. You were president of the senior class in the district high school when I was a freshman. Glad to see you, Betty."

"Good to see an old schoolmate." Her handshake was firm. "I wanted to talk to you before you asked Mother about the burglary. She has her good days and her bad days. This one's a bit middling. Don't be surprised if you get an odd answer or two."

"I don't need to even bother her if you know the answers," Palmer admitted. "All the other items that were stolen are pretty obvious. Easy to pawn. But a Cracker Jack ring?"

"Here," Adamson said with a smile, "you ask her about it."

Palmer introduced himself to Mrs. Churchfield deferentially. The woman eyed him speculatively then asked in a happy voice, "Betty, is this your young man come a courtin'?"

Her daughter turned crimson. "No, no, Mother. That's Julius. This is Chief Palmer. From Dixon Mills. He wants to know about your ring."

Palmer wasn't sure if he should be insulted that Mrs. Churchfield was equating him with Julie Sherman and his beer belly or roar with laughter, but instead bit his lip and kept his composure. Wait till he saw Sherman next day!

"My ring?" For a moment Mildred Churchfield's face clouded, then she came out as sunny as a spring day. "It was a keepsake! My young man gave it to me. Fifty years ago it was."

Palmer nodded his head to her deferentially. "Yes, ma'am."

"It was because of Mother," the elderly lady said with a faraway look coming over her face. "We didn't...you know, do like the young people today. None of that 'going steady' mischief. But Beau and I were in love. He couldn't give me a proper ring. Mother would have objected. He gave me the Cracker Jack ring instead."

Betty Adamson gave him a warning glance, but he realized he was already losing her mother's attention. "Was that his name, ma'am? Beau?"

But she was gone into the mists. "Always looked like he stepped out of a bandbox. Tall as the sky." And she continued talking about the past as if it were yesterday and while Palmer discreetly stepped away to chat with Mrs. Adamson. There was no lock to jimmy here as in the last two places; they'd never had to lock their doors before, Betty Adamson said in rueful surprise. They were off the main road and rarely saw anyone, not even hoboes. Whomever had stolen the goods had just walked in and taken them.

"Was there anything unique about the Cracker Jack ring?" Palmer asked curiously. "Something carved on it? Hidden inside?"

She shook her head. "Common metal ring, with a red glass 'stone.' Cheap, thin gold band."

"Damnedest thing I ever heard." Palmer colored. "Sorry, Betty."

"Damnedest thing I ever heard, too," she said with a smile.

Perturbed, he made his farewells, scuffing back to the car in deep thought. As he headed back out to the shortcut, the setting sun glinted through the stark trunks of the trees, making him flinch so that he almost missed what came next.

Next to the tree he had collided with early that morning was the dog. He sat next to its scraped trunk with an insouciant expression until the police car approached, then he rose, inclined his ears forward, and gave a slow wave of his tail.

Palmer leaned to the right and unlatched and pushed open the passenger door. "Where have you been? I've got two cops thinking I'm nuts talking about an imaginary dog."

The German Shepherd leaped gracefully in the passenger seat, and further impressed him by pulling the door shut with his teeth via the window crank. "Good trick. Who taught that to you?" Then he shook his head. "Listen to me. As if you're going to answer. Sit now, Duke."

Duke did him one better by lying down on the passenger side of the bench seat, not stirring as Palmer drove the remainder of the way home. He lived in a small cabin not far from the police station; this had been a waystation back in Dixon Mills' pioneer days, slowly modernized by Palmer from his early days on his own. Tired now, and a bit sore about the neck after the jolt against the tree in the morning, he let himself in, Duke trotting beside him as if he had always lived there.

Normally he stopped at one of the cafes on Main Street for his supper, or occasionally dropped in at Andrew Sellers' clinic, but with a dog with him he hadn't wanted to do either. Now he rummaged in the pine kitchen cupboards and came up with a can of Dinty Moore beef stew which he scooped out for Duke and a second can of hearty chicken stew, which he put in a pan on the gas stove and set to heat.

"Stick around and I'll get you something better than canned stew," he advised the dog, and went into his bedroom to change clothing. When he came out in blue plaid pajama bottoms and a worn tattletale gray undershirt, the dog was still standing by the bowl of stew. "Go on, eat up." But the dog did not stir until Palmer had scraped the contents of his pan into a bowl, pulled a bottle of beer from the refrigerator, then sat down at the table to eat. Then Duke began to work on the stew daintily, as if used to posh living. Palmer would hardly describe the accommodations as such; it was clearly a bachelor's home, only softened by objects inherited from his parents' home after his father had died and slipcovers and pillows made for him by his sister.

Palmer eyed the Shepherd as he finished the bowl. "Can't get over you. You act like a trained police dog. Someone must be missing you. C'mere."

Duke sat patiently while his ears were checked; Palmer knew they tattooed the inside of police and military dogs' ears. But the pinkish black interior was unblemished. Curious, he checked the dog's feet. Duke's nails were worn down as if in near constant contact with pavement, his leathery grey pads sketched with old scars. He gave Duke a grave look, then threw up his hands.

Duke took the opportunity to pick up the bowl in which his food had been in and disappeared into the kitchen. When Palmer followed him, curious, carrying his own bowl and spoon (which normally would have stayed on the end table until it became crusty and disgusting, whereupon he would reluctantly wash it), he found Duke on his hind legs, gently depositing the bowl into the sink. He took it as his cue to wash both dishes and the spoon, and when he turned to the stove he found Duke standing behind him holding the pan in his mouth.

"All right, you win," and he washed the pan as well, leaving the dishes to drain on a ragged terry cloth towel laid on the drainboard for that purpose.

Duke was standing behind him again, this time with a dishcloth in his mouth.

"What are you, my grandmother?" The German Shepherd simply blinked at him. So he wiped everything and put it away, while Duke supervised him with a doggy grin.

Now he went to the piano. He flicked at the sheet music left out on the music rack, then started playing by ear, Chopin's "Revolutionary," instead. He smiled when the dog sidled up to his small upright piano, ears forward, tongue lolling.

"And you have taste," Palmer added.

He thought again about the letter. He was more restless than anyone knew since the departure of Ruth Warner, despite several ladies who had attempted to lift him from his low state. Two had simply abandoned him while Carolyn Fournier had offered him a shoulder, as it were, to cry on if he needed and companionship if he didn't and had not pushed. He'd never thought of leaving Dixon Mills before; he always assumed he'd be here like his father, and his father before him, going back to the days when old man Dixon erected his grist mill at Silver Falls and ground the corn from the surrounding farms, corn hauled by oxen and mules, his clientele mostly straight-talking Yankees, with a smattering of French and Native refugees from La Canada.

He stopped his piano playing when he saw Duke flick out of the room and then come back in. A pair of threadbare slippers were in his mouth. Bemused, he fitted his feet into them, then shifted positions to the sofa, where he sat petted Duke for a long while, staring out the window. At about ten o'clock, he got up to take a shower before bed. When he returned to the living room with an old, thick Hudson's Bay blanket, he thought the dog had vanished again; the front door was half-ajar. But Duke was just bedding down under the eave of the entryway. Palmer tossed the blanket down nevertheless.

"I get it," he said sympathetically. "I don't like feeling trapped either."

* * * * *

"Who's your friend?" asked a familiar deep voice as Palmer sipped his coffee on the rustic bench outside Ed's Café, with Duke lying at his feet. He cocked one dark eyebrow up to see Simon Locke grinning at him, then holding his hand out for the dog to sniff.

"Beats me. Found him on the road to Kingsbridge yesterday—or rather he found me. You're out early."

"Exactly the opposite; I haven't been to bed."

"Don't tell me Jimmy Morgan's sick again."

"His sister this time. They both need their tonsils out."

"Hey, you got a minute?"

"Shoot." Locke paused at Palmer's face, then grinned. "Not literally, of course."

Palmer didn't even hazard a sarcastic smile back. "What do you know about antisocial psychology?"

Locke sat down next to him, plunking his doctor's bag on the seat as if it were too heavy. At this time of the morning—the sun was barely over the horizon, peeking over the low roof of the general store—it probably was, Palmer surmised. "Criminal type? As much as any doctor doing his residency and not matriculating as a psychologist. What's going on?"

Palmer explained about the burglaries and the odd item stolen each time. When he finished, Locke had his lips pursed in puzzlement.

"If this was a string of murders, it might be understandable," he said slowly. "Some of these killers like to keep trophies from their victims. It's particularly grim, especially when the victims are children. I don't think I've ever heard of a burglar keeping trophies, although I'm sure it's possible. Abnormal behavior comes in all flavors."

"That's what I thought," Palmer scowled. "Thanks."

"Dan, whomever's doing this will slip up. The trophy aspect makes it unique. I think that's where your guy will make his mistake and you'll be able to get him."

Palmer looked up sourly. "I wish I was that sure. Want to switch places? You track down this guy, I'll go home and sleep."

Locke turned on one of his 100-watt grins, the type that had everyone from Evie Muller to Carrie Morgan turning into puddles of mush. "Not me. You keep them law-abiding, I'll keep them well. And now I'm ready for a shower and the sack."

"Yeah, I need to get going myself."

"Oh...Mrs. Wynn said if I saw you she wanted me to ask if you were coming to Thanksgiving dinner. She needs to buy the turkey soon."

Palmer paused. Something else he'd put on hold upon arrival of the letter. "I...uh, still don't know. Sometimes my sister invites me to dinner at the last minute; it depends on how much of a houseful she has. I wouldn't want to tell Mrs. Wynn I was coming and then have to bow out."

"Just so I can tell her that I asked," Locke responded. He hefted up his satchel and was gone.

Palmer dropped the cup in the dishpan Ed left outside and looked ruefully at the doughnut in his hand. "Guess we'll eat on the road, Duke."

* * * * *

The drive was much the same as the day before, sans the clouds and the tree, although Palmer stuck to using Harriman Lane. Until, headed on the last stretch for Kingsbridge, Duke alerted.

He'd been sitting quietly in the front passenger seat, when suddenly he leaped to his feet, even in the small space with a catlike grace, whipping around and barking urgently out the window. Palmer, startled, pulled the police car to the right and applied the brake; as soon as he slowed down Duke disappeared out the open window.

Then he recognized the place: it was a few hundred yards up the road from where he had swerved to avoid the deer yesterday. He'd spotted the fresh white scar on the tree just a second ago.

What the hell?

Duke was barking from inside the trees and he heard shouting now, a man's voice. Hardly paying attention to what he was doing, he threw the car into park, grabbed his keys, and sprinted into the woods, doing the same dance as 24 hours earlier, skirting fallen logs, leaping branches, avoiding nettles. A branch slapped his face and thereafter he negotiated a tricky slope with his eyes down until a voice bellowed "Stop, you!"

When he looked up there was a rifle pointed directly at him. Had you asked him at that second who was at the other end, all he could have described was the huge round opening of the barrel. Then his training kicked in. The hole was small; probably only a .22. And the person carrying it...

"Mr. Bellaby?" he asked, with an incredulous squeak that made him wince internally.

The elderly man started, squinted at him. "Do I know you?"

Palmer took a deep breath, made his voice calm and gently monotone. "We met yesterday, sir. You'd twisted your ankle. I helped you up."

Bellaby still looked puzzled. "Yesterday?"

Duke appeared at his side, tense but not growling, indeed not appearing aggressive at all, just watchful. Palmer continued, "You met Duke here, too, remember?"

The confused expression faded from Bellaby's eyes and he lowered the gun. "I...do remember now. Can't imagine why I forgot."

Palmer gave a depreciating shrug. "At this time of the morning, I'm not exactly at my best myself." Duke relaxed, wagged his tail, and stepped forward to nuzzle Bellaby's free hand. "Can Duke and I walk you back to your house? Your ankle must still be hurting."

Bellaby tilted the rifle up so that he was carrying it in a safe position, with the barrel pointed upward and his hand away from the trigger, as Palmer had been taught as a boy, and he relaxed slightly. Maybe "Casanova Earl" had just awakened and was still sleep-fogged. "That's nice of you, mister. I'd like to stop over at my shed first to get a tool if you don't mind."

Palmer shook his head, managed a friendly smile. "Not at all."

Duke trotted ahead of them as he sauntered companionably at Bellaby's side, occasionally glancing backward to make certain they were still behind him. Palmer schooled his walk to a slow pace, although he was still wary and kept one careful eye on the rifle. When Bellaby set it down to open the shed, Palmer picked it up, resting it on his shoulder, hoping the old man would not ask for it back.

Once again Duke began sniffing around the shed door, his prick-ears as far forward as possible, tail motionless behind him. Bellaby glared at him as he emerged from the shed with a picking net. "For a dog you're about as nosy as that old biddy Evelyn Rhodie."

Palmer smothered a laugh. "What's the net for, Mr. Bellaby?"

"My nephew's picking apples for me," was the gruff response. "He's been doing a lot of work for me lately."

Apples? In November? Palmer made a note to talk to Johnnie...Bellaby?...about his uncle. Could be the old man was ill, or starting to suffer from dementia? And once again he doubted Johnnie was doing any farm work at all.

Bellaby said nothing about the rifle; in fact he seemed surprised when Palmer set it down, butt first, leaned near one of the front windows, as if he had not seen it before. He longed to bring it inside and put it away somewhere, but the rust-spotted metal doorknob didn't turn when he tried it. With quick eyes he noted the uneven boards of the porch, and, looking through the grimy windows between tattered calico curtains, could see only disorder and dirt inside. Definitely someone in social services needed to visit Earl Bellaby.

At this moment, however, he bid Bellaby farewell and walked down the creaking stairs with Duke at his side, giving the man a wave of his hand. Bellaby was standing motionless on the porch and Palmer felt momentarily uneasy.

"C'mon, Duke," he said finally. "Let's get back to work."

* * * * *

During the walk back to the car and throughout the remainder of the drive, he had intended to review what he found out yesterday, to decide what was important to tell Fisher and Sherman. But his mind kept sliding back to skinny Earl Bellaby looking out at him, the incongruous picking net in one hand, and the memory of the rifle.

Duke balked at going into the Kingsbridge Police Station. When Palmer opened the door to the patrol car, Duke remained stubbornly seated in the passenger seat.

"What's eating you?" Palmer asked acidly. "First you can't wait to lead me to a crazy old man, now you won't go inside where I have business. I don't get you at all."

The dark eyes that looked into his blinked, and then gave him an earnest stare. Palmer sighed. "All right, stay there then. I'll try not to mention my imaginary dog."

He could have sworn the dog nodded at him, almost imperceptibly, then lay down. His mind was whirling with Cracker Jack rings, elderly old goats and tool sheds, and enigmatic dogs as he walked from the bright autumn day into the nondescript gloom of the old house turned town hall.

Now what was Billy Fisher doing there?

Palmer stopped stock still in his tracks as he saw Fisher the younger with his ear inclined to the door of his brother's office. His face seemed a bit wolfish in the shadows of the inadequately lighted space, tense. Otherwise the dim hallway was empty.

"What's up, Billy?"

Palmer's voice boomed so loudly in the high-ceilinged corridor that Charley's brother leaped backward, his eyes stark in a white face. A second later the door opened and Sherman thrust his leonine head out. "You'll wake the dead, Dan." Then he noticed Billy standing frozen in the corridor, twisting his hands, staring at Palmer. "What's going on?"

Palmer chucked his chin at Billy. "Ask him why he was listening at your door."

"C'mon, Dan," Sherman clucked. "Billy hangs around here all the time."

"Why not just come in your office and talk to you?"

"Jesus, Dan, what's got you all up in arms this morning?"

Palmer bit back the words that were rising in his throat. You've asked me to help on a crazy mystery with a lunatic who steals Cracker Jack rings, there's a damn disappearing dog, a nutcase aims a rifle at me and forgets he met me the day before, and I'm thinking about making the biggest decision of my life. Why shouldn't I be "up in arms?"

Sherman responded to his silence by turning to Billy. "Here, go to Dorothy and get a couple of cups of joe and some doughnuts. Dan here looks like he needs a caffeine fix."

Billy swallowed, then disappeared, and Sherman held the door open for Palmer. Fisher was looking up from his desk, puzzled.

"Look," he said, before Sherman could speak, "I only wondered why Billy was listening at your door."

Fisher looked questioningly at Sherman, then back at Palmer. "What are you thinking, Dan?"

"I'm just considering possibilities, that's all."

"Because Billy's been in juvie?"

"When you first called me, you said you were looking for fresh ideas."

"It's crazy, Dan," Fisher said angrily, rising. "Billy's been clean for months. He just got into a bad crowd. And he never stole anything, just got drunk and broke a couple of windows."

Palmer put up his hands, palms outward. "Possibilities." He paused. "Look, I did those interviews yesterday, liked you asked, treaded the same ground, got the same answers, which were none. I walk in here and see your brother listening at your door. Why?"

"I don't know!" Fisher shouted. "But it has damn well nothing to do with any robberies."

"I didn't take anything!" Billy said loudly.

Three heads turned. The younger Fisher was in the doorway, pale and staring, holding a cardboard drinks holder with four paper cups of coffee, with four doughnuts in a paper bag clutched under it with his right hand. "I was listening to see if you heard about last night." He looked defiantly at Fisher. "I violated my parole. I had a beer down at the Tontine."

Fisher scowled. "I thought I told you..."

"...to stay away from that place," Billy mimicked. "I know. But that's where Jess and Tom wanted to go. Don't I have a right to see my friends now that I'm home?"

Fisher snatched the tray from him, and the doughnuts fell to the floor. Palmer scooped the bag up quietly and set them on Sherman's desk. "No, the fact is that you don't. I spoke up for you, Billy! I told them you'd stay out of trouble."

"I didn't get in any trouble!" Billy retorted. "Jess and Tom and I sat down and had a beer. One beer. We just talked and nobody got rowdy. I was just afraid old Jacques might tell on me. He gave me a chewing out when he found out Etienne let me have the beer."

Sherman leaned sideways and said under his breath to Palmer, "Jacques Moreau runs the Tontine tap down on Route 27 with his brother Etienne." Aloud he said, "Etienne knows better, and good for Jacques. They both should have thrown you out."

"They didn't have time to bother with me," Billy retorted. "Some dude named Johnnie had Etienne all riled up. Think he was drunk."

Palmer lifted his head, alert. "Big husky guy? Red hair?"

"Yeah, that was him. Why?"

"He's Earl Bellaby's nephew," Palmer said. "Bellaby told me he's 'helping out on the farm.' I didn't see much sign of it. Oh, I wanted to talk with someone about Bellaby, maybe Daisy Watson up at County Services in Briarton. I think something's wrong with him. You remember I told you I helped him out yesterday after he hurt his ankle? Well, this morning I ran into him and he didn't recognize me. In fact he pointed a rifle at me until I reminded him we'd met."

Sherman looked puzzled. "Earl? Pointed a gun at you? I don't think I've ever heard anyone complain of old Casanova Earl being violent before."

"Surprised the heck out of me, too," Palmer admitted. "And then when he did let me and...well, let me walk him back to his house, he had to stop by his shed again for an apple picking net. Told me his nephew was going to use it for picking apples."

"In November?" Fisher asked, incredulous.

"Swear to God."

"That does sound weird. Well, we'll talk to Daisy or someone at the county seat after we resolve these burglaries. Funny thing, though..."

"This whole case is funny," Palmer said, relaxing a little. He turned his head to Billy. "Look, I'm sorry. I jumped to a conclusion and that wasn't fair."

Billy looked down. "It's okay. I guess it did look kind of suspicious, and after I hotwired your car and all..."

"Dan-" Sherman said abruptly. "Are you sure Bellaby said this Johnnie character was his nephew?"

"He did, and Johnnie said it himself to me."

Sherman sat back on his desk, pensive. "The thing is, old Casanova Earl only had one sister and no brothers. And I'm pretty sure she died a spinster."

Palmer arched his eyebrow. "That doesn't mean she couldn't have had a son, does it?"

Fisher gave a whoop of laughter. "Dan, you never met Cassandra Bellaby. I can't imagine her getting that close to any guy, never mind doing what needed to be done to have a child. She hated men."

"All I know is what I heard. Anyway, I want to make sure Daisy knows about the old guy, okay? I've seen older people pushed around by younger ones. It's not pretty."

"I'll make a note to call her," Sherman said, reaching back for a pad and pen. "Now, about our more immediate problem..."

A thunderous volley of dog barks came from outside, so loud and sharp that they penetrated the closed windows fronted with storm glass. Then brakes screeched.

Duke! Palmer bolted out the door and out the front, to see a sedan disappearing down the road and Duke standing outside the police car. His body was tense, nose pointed forward down the road and each bark shook his body from head to tail.

"That your imaginary dog, Dan?" Sherman said from behind him.

"Yeah, and barking after a not-so-imaginary car," Palmer said grimly. "I swear it was blue, like the car Johnnie had when I saw him yesterday at Bellaby's farm. I need to go check something out. I'll be back."

As he sprinted for the car, Duke loped toward him, circled him, leading him back to the vehicle. "Yeah, I know." He opened the passenger door. "Come on. Let's go."

The dog sat in the passenger seat tensely as Dan pressed the accelerator as far as he dared in the town limits, eyes directly forward, fur spiked on his neck like dark needles. As the trim lawns receded to make way for businesses and then woods, Dan's eyes darted from one side to the other. The sedan had been burning rubber going through the town center, but it shouldn't have gotten so far ahead...

Duke woofed and pawed at his arm, and he braked, puzzled. No car here at all; they were back at the spot where he'd leaped out the window that morning.

"Don't tell me that old man is out here with his rifle again," he said aloud, as if Duke could answer him, but to his surprise the big Shepherd acted as if he had indeed understood, pawing his right arm again with his rough pads and worn toenails, giving an urgent whine.

"All right," Palmer said finally. "But this time I'm keeping my hand on my gun."

This time Duke proceeded at a more discreet pace. He stepped purposefully through the deadfall of the forest and Palmer noticed he was trying hard to make no sound. Unconsciously he copied the animal, recalling childhood woodcraft taught to him by his uncle Daniel, a clever hunter and raconteur. His uncle had trapped for a living, back in the long-ago days when the wolves, lynx, and bears lived in the dark corners of the forest and bounties were common.

They were heading right for Bellaby's cockeyed shed; indeed Duke stepped up his pace and pawed at the door. Palmer stopped and considered. Could it be...was this what Duke had been trying to lead him to all along, not the elderly man but this shed? He tried to remember what he had seen inside: tools hung up. Burlap bags. Fox traps. Perhaps a tool bench?

Duke scratched again and he wondered how he would get in; hadn't Bellaby unlocked and locked it when they first met?

Memories were crowding in his head.

An old Pontiac sedan ... "Get out of the way, dog, or I'll take back what I said about you being smart." ... “Comes by to help me with big projects...” Casanova Earl ... "Always looked like he stepped out of a bandbox. Tall as the sky." ... "For a dog you're about as nosy as that old biddy Evelyn Rhodie." ... "He's been doing a lot of work for me lately."

He and Duke had taken Bellaby by surprise this morning. Not only was the padlock—a new padlock, still shiny, odd for a shed as old and in the weather as this one—already open, but the hasp hadn't even been closed. Palmer put his hand on the rusted slat of metal and pulled, and the shed came open easily.

Even with a weak sun spilling on it, the interior was illuminated. Fox traps. A half-tipped handmade workbench with splintered legs. Dirt-begrimed spades and shovels. A hoe with a half-rotted wooden handle. A coffeepot-sized old brown box full of rusted sixpenny nails. A battered rake with half the tines gone. The post hole digger tossed in a corner. Palmer smirked. He hadn't thought young Johnnie had been doing much work. And the burlap sacks. One was fallen over, revealing something shiny and silver.

"What's a salver?"

"A silver tray."

He took three steps inside, with Duke bounding in ahead of him, and stubbed his toe on yet another small burlap bag, which fell over. He looked down, picked up the bag, which was so rotted that it all but fell apart, revealing...

"A cheap ring, silver and scratched," Palmer said aloud to Duke, who stared at him intently, "a black and white photograph of Elizabeth Stalmaster who died back in 1959...a plain old woolen scarf from Woolworth's...a tea pot from the five and dime, now slightly nicked...and, well, what do you know? a Cracker Jack ring made of cheap pot metal, with a red stone..."

Duke lunged forward, snarling, just as something very hard and solid struck the back of Palmer's head.

* * * * *

"Christ," Palmer muttered through his teeth.

He hadn't been unconscious long, but long enough. His hands were tied behind him with some painfully prickly bond and his head felt like a bell tower in which his ears were tolling a death knell. He struggled, then fell quiet, trying to overcome the pain. It was only then he became aware of two loud voices outside the shed.

"You stupid jackass!" Bellaby, sounding much stronger than he had this morning. "What did you do that for?"

"Calm down, pop." "Johnnie," jeering. "You want to get caught?"

"We're already caught, you nincompoop!" bellowed the older man. "He's not only seen what you did, but you knocked him out!"

"No sweat off my back, man," Johnnie responded easily. "I got connections. I'll get my stuff and be on my way."

"And leave me to face the music!"

To Palmer's surprise, Bellaby added angrily, "What did you go steal that other stuff for? I paid you well enough to take only my things!"

"Get off, pop," Johnnie laughed. "You figure I was going to go to the trouble and the danger of breaking into folks' homes for your stupid little mementoes and not make a profit for me? Man, you're as stupid as those Kingsbridge pigs." He paused. "Ol' Dan Palmer here, he was a little smarter."

"You've ruined me!" Bellaby wailed, his voice suddenly going plaintive.

Johnnie laughed. "Dude, you're pathetic. A stupid, pathetic old man who wanted his romantic trophies back." He called the old man an epithet that made Palmer flinch. "Get out of my way."

"You ain't going to shoot him!"

Palmer's blood ran cold. He was lying on his right side and could feel all too clearly that his revolver was no longer in its holster.

"I'm not going to shoot anyone, you stupid bastard. Bad enough I got caught when this dude came snooping around, him and his stupid dog. I'm not going up on a murder charge. I've disappeared before, I can do it again."

Now Bellaby was whining like a child. "All I wanted were my things. Those ladies done me wrong. I deserved 'em back. Don't shoot me, don't shoot me." He must have been blocking the door, for Palmer heard something hit the wood with a sickening CHUNK, and then a cry of pain was heard. After a few seconds the door opened and Palmer snapped his eyes shut after seeing a black figure silhouetted in the doorway. Johnnie gave him a not-gentle nudge with one foot. "You awake, pig?"

Palmer slowed his breath, made not a sound.

"Good. Gives me time to get away. Stupid old man. 'Casanova Earl.' That's what he told me they called him. Said he was a Romeo in his day, and the ladies all loved him, then spurned him. 'Spurned.' That's what he said, pig—what a hoot. So he wanted his little gifts back. Like I was going to take all that time to break in to a bunch of houses and not take something for myself."

He was evidently lifting one of the burlap bags, for he grunted. He pushed past Palmer with a rude kick, adding another bruise in his ribs to the tally.

There was no sound from Bellaby, still none from Duke. Had Johnnie killed them despite his protestations?

The red-haired man came back, this time with no kicks, hoisting out another burlap bag. This one was so heavy it swung past Palmer's slitted eyes. He almost recoiled at the damp, rotting scent, but schooled himself to stay still.

At long last Palmer heard the roar of a badly-timed car engine. It was revved and then the sound moved away, leaving the stink of exhaust.

Would his head never stop pounding? When he opened his eyes fully the light blazing into the open shed made the throb even worse. His right cheek was rubbed raw in the dirt and now that he could concentrate a bit better he felt wetness at the back of his head.

No one would ever find him in the shed. At least not before "Johnnie"—or whatever he was really called—got away. He tried to push his way forward with his feet, which moved him a bare inch and made his head scream.

It was then he heard the panting noise.

"Duke?" His voice was hoarse.

More panting. The brief scent of dog breath. And then a welcome whine and a warm tongue licking his face.

"Thank God." Those old television series came to mind, the ones with the faithful mutt who led help to their injured masters. Only a story? He'd seen Duke do some clever things. "Duke. Get help. Go get help. Go back to the police station."

The dog whined again, and then the tongue was gone. Had he understood?

Then Palmer felt something soft touch his hands, then something hard. There was a tug at his wrists. "Duke?"

A whine. A worried, muffled growl. More tugging. Wetness. Palmer's ears still rang. He might have even passed out, because when he was aware again, the dog was licking him again, and his hands were loose. He pulled at one arm, then the other until his hands came free of abrasive rope.

It took him an age—or so it seemed—to get up. An age in which his head wobbled and his stomach roiled and the pain when he moved almost drove him to cry out. Duke stayed beside him, bracing him up, licking his face when he needed it most, nudging him when he almost passed out again. He made it to his knees, then up on his feet, dizzy and nauseated, staggering from the shed to find Bellaby sprawled prone outside the shed, the back of his head bloodied.

Palmer lowered himself to his knees, his hands fumbling for Bellaby's wrist. He said thickly, "He's got a pulse, Duke."

There were indistinct, loud noises in the distance, carried over the autumn-quiet trees as if magnified. The dog barked, once, twice, and Palmer turned his head, wincing. If Johnnie was returning, how could he defend himself—he patted his holster and his service revolver was indeed gone. What would big-bug Captain Robert Piekowski think of him now, letting a clown like that get the drop on him?

One moment Duke stood ramrod stiff before him, a barrier between him and the world, his black-and-silver body tense. Then he was gone. Palmer reached for him, the world slid sideways...and then Palmer passed out.

* * * * *

"Welcome back, Chief," said a familiar voice.

Palmer had to blink twice, then flinched as Kingsbridge's lone G.P. Henry Abbott cleaned the wound at the back of his neck. Charley Fisher was at his left, holding him steady on an examining table with the rear portion raised to support him. Sitting in front of him on an old wooden chair, calmly performing the same operation on a nasty-looking cut on Duke's white left eyebrow, was Simon Locke.

"What are you doing here?" he rasped. "Henry finally take pity on Andrew and hire you away?"

Locke gave a lazy smile. "I was in the general store talking to Bert when he got the call you'd been hurt. Figured I'd tag along. As hard as your head is, I thought Doc Abbott might need some help." He looked down at Duke. "Found another patient instead."

Palmer struggled against Fisher's hands. "Bellaby..."

"Earl's fine, Dan," Fisher responded firmly. "Got a concussion, like you. They took him off to Hearkness about fifteen minutes ago. When we got him conscious, he wasn't making any sense. We thought it was the conk on the head, then we remembered what you said about him not recognizing you this morning. Doc Abbott thought a neurologist should look at him."

Abbott, a slim middle-aged man with fair hair parted in the fashion of several decades earlier, dressed in a prim dark suit and narrow tie, added, "I've been worried about him for a while now. Not that the old fool ever came to see me. But I'd heard from his neighbors that he was forgetting things and babbling oddly about the past. Heck, he asked me about the turkey shoot last week and we haven't done a turkey shoot in near 20 years."

"He hired this Johnnie guy to steal some mementoes he'd given to his old girlfriends." Palmer said thickly. "Said they'd 'spurned' him and he wanted them back. Except 'Johnnie' took advantage of the opportunity and stole things for himself, too. He was keeping them in Bellaby's shed."

"He told you this?" Julius Sherman asked, framed in the doorway of Abbott's examining room.

"I was playing dead. Like most of these clowns he was really proud of how he put one over on us 'pigs' and was bragging aloud about it."

"Waddya know," Sherman said mildly. "So some of what Casanova Earl said did make sense. He was talking about Millie Churchfield. Something like 'You can't keep it, you old witch. You turned me down and you can't have the ring.'"

"If he's the 'Beau' Mildred was going on about," Palmer said with a rasp, "her daughter told me it was more the other way around. He still wanted to play the field."

Locke gave Duke a pat, then rose, filled the plastic cup next to Abbott's examining room sink, and handed Palmer the cup. "You sound like you could use this." As the water was greedily guzzled, Locke added, "As he got older, he probably resented being alone. But he couldn't blame himself, so he turned the story around in his head and blamed someone else. A classic syndrome."

Palmer handed the cup back, his right hand still unsteady. "What about this 'Johnnie' clown? He got away, didn't he? And with my revolver to boot. Duke wasn't quick enough biting the ropes off my wrists. He's got to be caught before he hurts someone."

Fisher looked down at the dog, impressed. "The dog untied you?"

"He did. It's how I got out of the shed."

"Damn." Fisher squatted to look Duke over appraisingly, with the dog regarding him with grave eyes. "You going to keep him, Dan?"

Palmer responded unexpectedly, "If he'll have me." A pause. "Look, what are you doing to track down this guy? Just because he didn't use his gun on me or Bellaby or the dog doesn't mean he won't use it on someone else."

Sherman laughed. "Relax, Danny boy. He isn't loose and we have your piece back. And he did try to use it on us, but your buddy here–" and he nodded at the German Shepherd, "saved us. Came racing through the woods and knocked the son of a bitch ass over teakettle. Your revolver did the nicest two-and-a-half gainer I've ever seen. The perp's locked in the jail now."

Palmer rubbed at his head. "That's impossible. He had a big head start, at least twenty minutes...wait, did that old junker of his break down? It sounded pretty rough when it drove off."

"Hey," Abbott remonstrated. "Stay still. I'm trying to sew you up here."

"After you lit out after the dog," Sherman explained, "Charley and I were worried about what you said about Casanova Earl, how he'd forgotten who you were and stuck a rifle in your face. We were discussing what to do when we got a fax in from Briarton. They had some trouble with break-ins there last month, but they had a suspect—your Johnnie Bellaby's real name is Richard Thompson—who'd vanished, and I'd sent them an inquiry about it. You know faxes—take forever to come through. It was a big dude with a beard, but of course in black and white, so we called Briarton back to ask if he had red hair. When they told us 'yes,' we realized you might have run into trouble and headed down to Bellaby's place."

"And that's the funny thing, Dan," Fisher broke in. "Thompson's car didn't break down. Turned out there was a whole pound of sixpenny nails strewn out on the road, just past the Bellaby driveway going toward Dixon Mills, right near where you hit that tree yesterday. Got the tires of that old Pontiac about thirteen times." With a grin he held up an old brown cardboard box, one end of it looking soggy and chewed. "We found this and the nails in the road. Nothing else. Looks like a varmint chewed on it." He chuckled. "In fact, his car came to a stop right before your squad car. He’d been trying to hotwire it when we came up and that’s when he pulled your piece and came on like Dillinger."

Locke arched one eyebrow. "You think some animal tossed a box of nails out on the road? I'm not a wildlife expert, but that sounds like a Roadrunner cartoon. Have you got some scrawny coyote hiding out in your woods?"

Sherman waved his hand dismissively. "I've seen porcupines do something similar in mountain cabins. It's a mess. They get into food stores because they love salt and will pick up anything that's been touched by salty human hands, and they can smell salt for miles. That box of nails could have been in Bellaby's shed. A porky picked it up and waddled off with it, the box broke open when he chewed on it for the salt and scattered the nails."

Palmer knew no nails had been across the road as he'd headed into Kingsbridge earlier. Old brown box of nails? There had been a box of nails in the shed...

His eyes shifted to Duke, but the dog only yawned. No. It couldn't be. Sure dogs open doors. Pick up bowls. They train them to. But scatter nails?

Duke gave him a cool gaze, slowly blinking.

I'm worse off than I figured, Palmer thought.

"There," Abbott said finally. "You have six stitches. Dr. Locke or Dr. Sellers can take them out in two weeks, or a week, whenever they see fit. In the meantime, I'm prescribing pain medication and at least a week of rest. No driving while you're taking the medication!"

Palmer felt near the back of his head gingerly, touching suture thread. "All right, I'll go home..."

Locke said firmly, "You will not."

"You can't boss me around, mister." Palmer flared.

"Damn well I can," Locke retorted. "I'm a citizen of Dixon Mills and you are our chief of police. It's my responsibility to see you stay well. And tonight you're staying at the clinic."

"Better listen to him, Dan," Sherman chuckled. "If you're taking that new job, how will you listen to a big-city boss if you can't manage taking orders from your own doctor?"

Locke looked startled. "Job offer?"

At dawn that morning, Daniel Palmer could have told you decisively that he hadn't decided yet. But now he retorted strongly, "Oh, hell, no. Like I'm going to be treated like a wet-behind-the-ears rookie till some big-city lunk thinks I can be trusted on the street. That would be worse than...taking orders from some big-city doctor."

The last six words were accompanied by a glare at Locke, who had the grace to smother a grin, but his eyes were dancing.

"I think you oughta listen to Dr. Locke, Dan," Fisher said soberly. "I can see the back of your head. I've seen raw hamburger look better."

"All right, all right," Palmer said grumpily, lowering his hand so he could stroke Duke's head. "What about Duke's stitches?"

"I used the absorbable type on him. They'll just dissolve after a few weeks."

And so Palmer spent the rest of the day at the clinic, for his health, not because, he insisted, Simon Locke and Andrew Sellers squawked over him like a couple of old hens. He spent most of the day dozing in the hospital bed while Flora brought him fruit juice and broth. He tried reading one of Locke's favorite murder mysteries, snorted at the police procedures, and tossed the book aside in favor of another nap. Duke was in and out of his room most of the day; Flora remarked approvingly on his house training and wonderingly on his uncanny ability to open doors. But he spent most of the time asleep beside Dan's bed, only waking when one of the doctors or Louise Wynn came in to check his vital signs and his vision and perform other tests that would confirm that his mild concussion was not developing into something more severe.

An unsmiling Locke checked him out "poll to sole," as Andrew Sellers had genially termed it, the next afternoon, looking for double vision, unsteady gait, balance difficulties. Palmer, with a smug face and a closed mouth, ran through the routine effortlessly.

"You win," Locke said. "You can go home. I'm setting off on afternoon rounds and I'll drive you. Either I or Dr. Sellers will check you out once a day. In the meantime..."

Palmer mimicked, "'If I have double vision or trouble balancing or nausea, I call immediately.' Yes, Mom."

"Dan..."

Palmer sighed. "Simon...I understand. I've no intention of dying if I don't have to. I just want to go home."

"Fair enough."

He slept quite a bit the remainder of that day, staring at television the rest of the time, noticing with amusement Duke's pricked-ear interest in the snowy images of a farm boy and a collie coming from the station in Burlington. In the morning he felt stronger, and by the third day was going about his regular routine, cooking his meals, sweeping the floor, playing piano, watching what few things on the idiot box that he liked. His favorite part of the day was going outside with Duke to tramp the woods behind his house, since by that third day, he was also bored out of his skull, and noticed signs of Duke being fidgety.

"I could go into the office tomorrow," he was musing aloud by sunset, as he was washing supper dishes after Andrew Sellers had stopped by and told him he must have the world's hardest head and he was getting along fine but for God's sake to take it easy. "Not go out, but go into the office. We could walk, you and me, Duke, an easy few blocks. Help Bert answer phones while he's on patrol. What do you think, Duke?"

The dog was gone.

Probably just needed to go out, Palmer thought to himself, then paused. That walk today—hadn't Duke seemed restless? He could see the dog wandering ahead of him, circling back, looking toward the horizon with wistful eyes.

He put down the pan he was washing and walked out the front door.

Duke was sitting in the middle of the driveway, looking out toward the sunset. Palmer swallowed, then covered the few steps between the two, and squatted down next to the big dog.

"This is it, huh?"

The German Shepherd gave him a steady look, then nuzzled his hand.

"So you stopped off to help me and now it's time to go?"

"Uffff."

"Well, thanks for the help." He gave the animal's head a rough caress, careful to avoid the cut over his eye, and then gave in to his feelings and gave him a tight hug around the neck. Duke licked him in return. "Take care of yourself, okay?"

The Shepherd rose, stretching his sleek black-and-silver form. With a parting nudge to Palmer's hand, he trotted down the darkening road.

"Traveling around from town to town,

Sometimes I think I'll settle down,

But I know I'd hunger to be free–

Rovin' is the only life for me."

For a moment he stopped, and turned his head, giving Palmer one last look that made the man's heart leap into his throat. And then he broke into a lope and vanished into the gathering dusk.

"A-driftin'. The world is my friend,

I'm travelin' along the road without end."

Palmer stood and watched the road until he could see nothing more, then walked back into the house, head down, lips pursed. He paused by the telephone, then dialed the clinic.

"Hello, Mrs. Wynn...no, I'm fine. In fact, I'm going into the office tomorrow to check out the paperwork pile on my desk and harass Bert while he's on patrol." He paused. “No, Louise, I am not intending to drive!" He paused again, took a deep breath. "Look...I just wanted to know—this Thanksgiving shindig you're planning...what can I bring?"

Back to Doctor Simon Locke page